Our Family’s Journey with LBD

I can't remember the point we realized that something was amiss with Mum; I just recall it seemed to happen quickly. She was eventually diagnosed with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), which often has a rapid or acute onset and that's how it seemed with her–one minute she was fine and the next she was anything but.

In hindsight the signs were starting to appear in 2009/2010 and by 2011 she was displaying some of the signs typically associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and most of the signs unique to DLB, which were not only baffling but upsetting—and quite frankly frightening at times.

· Repetitive questions. This wasn’t a big issue with Mum but she easily lost track of the time and was always asking what day it was.

· Losing things (or rather putting them somewhere safe!). We seemed to spend hours looking for things, in particular her glasses and purse.

· Unable to recognize her own home. She used to get very agitated as to why we had sold her house without her permission and was always asking to go home even when she was sitting in her own front room.

· She was very suspicious, often accusing us of various things, in particular stealing her purse and selling her house.

· Fluctuating cognition. One of the key feature of DLB is that the symptoms vary (fluctuate) widely day by day and even during the course of the day. One-minute Mum would be okay and then she would suddenly become confused, restless or agitated.

· Short attention span. Mum would start doing something, quickly lose focus and move onto something else and as a result the house was usually in a state of chaos.

· Dizzy spells. As a result of a drop in blood pressure, Mum would become dizzy when she stood up. Sometimes it would pass quickly but often, if we were out in unfamiliar surroundings, it wouldn’t and Mum started to have panic attacks as a result.

· Difficulty with depth / space perception. This is a particular issue going up or down stairs. She can't judge the depth of the drop or the width of the tread below so she tends to just stick her foot out and drop, invariably falling as a result if you’re not holding onto her.

· Unable to perform simple tasks. People with AD do not store information about what happens now so are unable to remember the present, whereas people with DLB have more trouble retrieving information that has already been stored. In addition, people with DLB tend to lose their thinking skills sooner than people with AD and as a result lose their ability to perform a series of tasks in the correct order. The most noticeable one was making a cup of tea or coffee, which from quite early on in her illness she was simply unable to do. You would be surprised by the number of possible variations there are to making a cup of coffee from putting the coffee straight into the kettle or putting water from the kettle straight into the jar of coffee, by passing the need for cups.

· Restless nights. Mum has talked and moved about in her sleep for as long as I can remember, which she continues to do. This is often a precursor to DLB.

· Visual hallucinations. Another key feature of DLB, we would often find Mum chatting away to someone/thing and most mornings she would get incredibly flustered insisting she needed to take a register of all the children in the kitchen.

· Illusions. Mum would incorrectly see a real object, such as a cushion, as something else, such as a cat, so you would often find her stroking and talking to a cushion.

· Delusions. Possibly as a result of her hallucinations, Mum was convinced that there were a group of strangers living on the ground floor, which in turn strengthened her conviction that it wasn’t her house.

· Shuffling walk. In the early stages this only tended to be noticeable if she was tired or stressed. She would lean forward and take little shuffling steps, often falling as a result.

· Agitation. Mum would become highly restless and agitated (often suddenly). It would usually start with questions as to why we had sold the house and no amount of reassurance that it was her house would settle her. This anxiety always increased around 4 pm, a phenomenon known as 'sundowning', which is ironically a more common feature of AD than DLB.

One of the biggest issues we faced was Mum’s utter refusal to accept there was a problem or to even discuss it in any way. It is imperative that work continues to remove the stigma from dementia not only to ensure that sufferers receive more help and understanding in the community but also to help them accept the illness without fear or embarrassment. Even now the very word dementia sends her into an episode of either extreme anger or sadness.

We eventually managed to get her to agree to a memory test by using good old fashioned emotional blackmail. She reluctantly agreed and was immediately plunged into a depression that lasted until we received the results. She was overjoyed and we were flabbergasted to learn that she had passed the test.

I can’t remember how Mum was the day she took the test but as one of the key features of DLB is that symptoms fluctuate—she must have been having a good day. In addition, although day-to-day memory is affected in people with DLB, typically it is less so in the early stages than in early AD which may explain how she managed to answer the questions they typically ask.

At this point I was fairly ignorant about dementia (I had never even heard of DLB) and was convinced that Mum had AD. I made repeated calls and visits to the doctors (alone as Mum refused to discuss the matter further), trying to describe Mum’s behavior but the physician was convinced she had depression. Through sheer persistence I finally managed to get a referral to a specialist. Two visits and a brain scan later in March 2012, we finally got a diagnosis albeit an incorrect one of mixed vascular dementia and AD. Mum was a relatively young 69 years old.

We were assigned a consultant psychiatrist (a different one to the one who made the diagnosis), a community psychiatric nurse (CPN) and an approved social worker (ASW). Mum also started a course of medication, including dementia medication, anxiety tablets and sedatives to help with the disturbed sleep.

We were naively hoping that the medication would calm Mum but it didn’t happen and her behavior deteriorated. Further changes were made to the medication dosage and the time the medication was administered to try and combat the ‘sundowning’ effect. We were very lucky that the psychiatrist knew a fair bit about DLB and around this time, following a home visit where he observed her behavior and asked us various questions, he changed the diagnosis to DLB. It is very important that DLB is correctly diagnosed as sufferers can have a severe reaction to certain ‘anti-psychotic’ drugs.

Although a key feature of DLB is fluctuating cognition, things such as changing medication, physical illness and stress will cause symptoms and behavior to deteriorate dramatically. I now think that it is likely that some of the things we were doing to try and help Mum were in fact making her condition worse. Her medication was constantly tinkered with, and she wasn’t eating or drinking much by this point, so she was probably dehydrated. We were always trying to reassure her that there wasn’t anybody else living in the house, something you should avoid doing as her hallucinations are very real to her. We were also trying to keep Mum engaged in the things she used to enjoy such as helping with the cooking, things that were simply beyond her, causing frustration and embarrassment. In hindsight everything we were doing was adding pressure to a system that was simply unable to cope.

By now her behavior was what I can only describe as manic, and we were all beyond stressed. She refused to stay in the house and soon as she got up in a morning she would be out the door to go ‘home’. We spent hours literally wandering the streets with her until she reached the point of exhaustion and we could take her home where she would sleep for a couple of hours. She also started approaching people in the street asking for help as she believed she was being followed.

Following an emergency call to the CPN it was agreed with a heavy heart that she needed to be hospitalized whilst they tried to get her medication combination right in a safe and secure environment. I will never forget the day we took Mum to the hospital in August 201—the worst day of my life. My sister and I took her and because Mum would never have willing agreed to go, we told her we were going to the chemist to sort out her tablets. She trustingly came along, like a lamb to the slaughter, and although we didn’t know it at the time, she would never return home. Mum was in the hospital for four months and spent much of her time trying to escape (she managed to make it as far as the car park on two occasions). As a result, she was sectioned, something else she would have hated if she had been well enough to realize what was happening.

After four months in the hospital we were told that Mum was as good as she was going to get and we needed to agree to the next steps, so a home visit was arranged with a member of staff from the hospital. The visit didn’t go well; Mum stumbled down a couple of stairs, quickly became agitated and started asking to go home. With a heavy heart we all agreed that Mum needed to go into a care home.

Finding a suitable home was made all the more stressful by the fact that the hospital staff and social services couldn’t agree on the type of home needed. Ideally Mum needed somewhere with no stairs and lots of room to ‘pace’ and most of the homes we looked at were unsuitable. Thankfully, as we were starting to run out of options we found a specialized ‘people-centered care’ dementia unit with a secure central garden area, and plenty of room to roam. We were lucky that places were available, and following a visit by the senior nurse from the home Mum was accepted.

When Mum first arrived in the home, she caused chaos and we were genuinely concerned that they wouldn’t be able to cope. They have an open bedroom door policy and Mum would wander into a bedroom, pick something up, get distracted and take it into the next bedroom resulting in everyone’s belongings being scattered to the four winds. She would also attempt to assist bedridden patients by either helping them out of bed or tucking them in, resulting in a risk of suffocation as she pulled the covers over people’s heads. Fortunately, the home was very good at adapting, labelling everyone’s possessions and placing pressure mats in the doors of all bedridden patients.

Mum has been in the home for over a year now and although her condition inevitably continues to deteriorate, she is as settled as she ever will be. She long ago lost the ability to form sentences (although she will chat away for hours—it rarely makes any sense) and she is now losing the ability to form words. She can’t quite work out how to use a knife and fork anymore so often eats with her fingers and now complains of muscle ache and fatigue even after a short walk.

Whilst the campaign to raise awareness has begun it is important that people understand about the lesser known dementias such as DLB. An understanding is crucial in being able to properly describe the symptoms to get an early, accurate diagnosis and to be able to provide relevant care. It is amazing how many people still associate memory loss as the key symptom of dementia, whereas in DLB it is probably the least significant aspect.

It never ceases to amaze me when I tell people that Mum has dementia how many ask ‘does she know who you are’. Sometimes Mum gets it right and will say “this is Emma, my eldest daughter”. Often I am introduced as her sister (even though she doesn’t have one) and I have even been her husband. But what I always get on visiting Mum is a big smile and a hug. So in answer to that question I always reply “yes she does, in the only way that matters”.

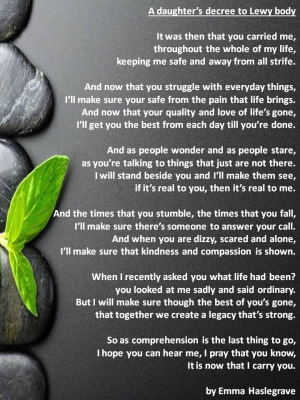

Personally I am starting to come to terms with Mum's illness, with what is and what will be. I cannot change it and I cannot go back, knowing what I now know, and make the journey easier or better for all of us. I believe that DLB is the cruelest dementia and for the sufferer this hideous disease will quickly take away the ability to do the things they enjoy, their quality of life. It will place an intolerable burden on their family and it will make them afraid in their own home. However, the fluctuating cognition can continue right to the end and Mum continues to have periods of awareness or ‘insight’. Sadly, as she is in a home, the chances of a family member being there when it happens are slim but I hold on to the fact that I may get some time with the Mum I used to know.

Another key feature of DLB is that comprehension is the last cognitive function to go so even when they can no longer communicate they may still understand what’s said. So I will continue to visit Mum, I will make sure that she is safe and I will tell her how much I love her in the hope that right to the end she will hear me and be able to remember for longer than the blink of an eye.

Since writing this story, Mum sadly died in September 2016 and my world changed forever. Mum’s journey through dementia changed my life and there are some memories that will haunt my dreams forever.

However, right until the very end of her life, Mum still recognized me as someone she knew and loved, proving that love really can conquer all, even the hideous disease that is dementia.

Emma Haslegrave

Jan 27, 2017